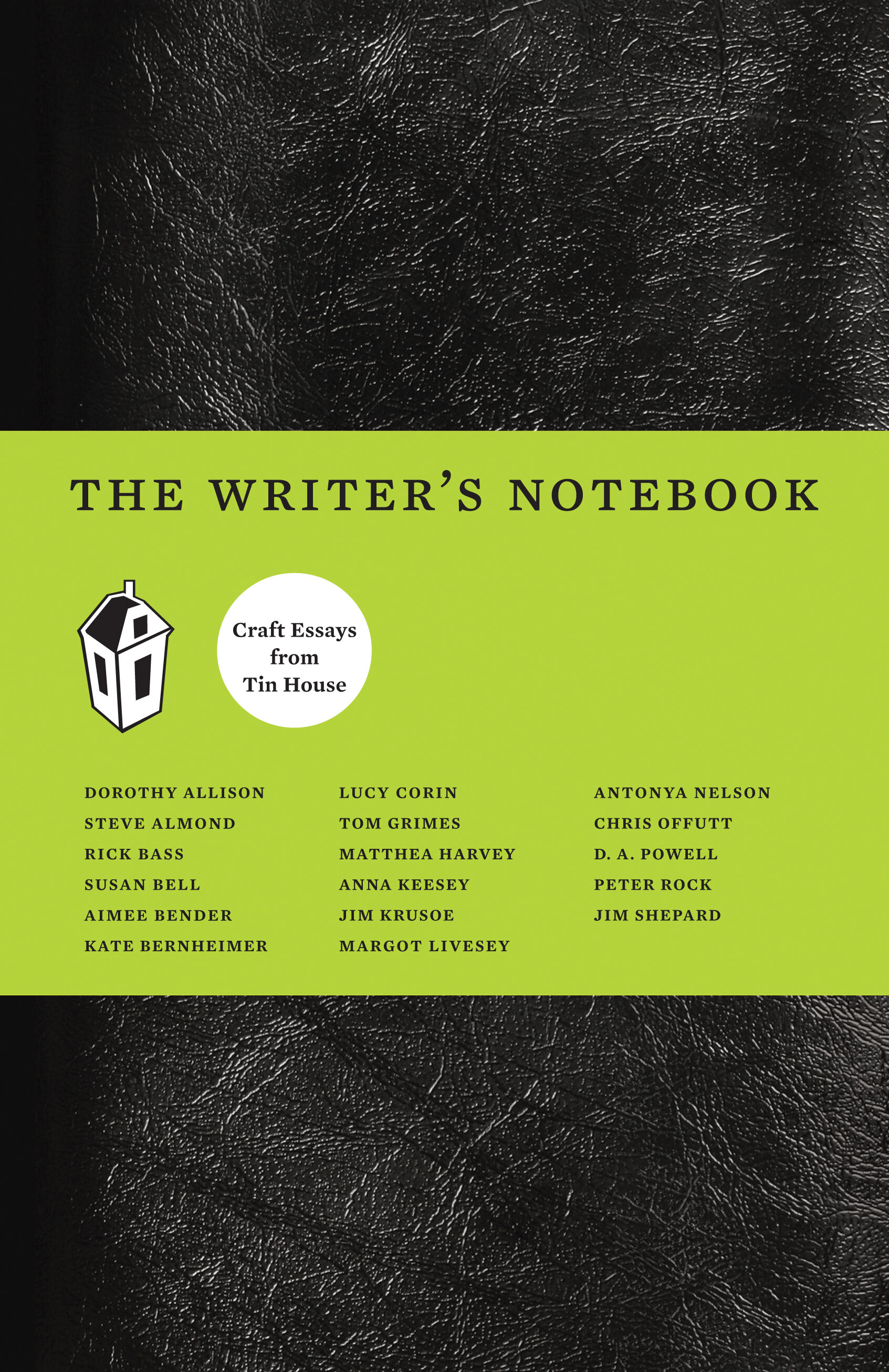

I’m a huge fan of THE WRITER’S NOTEBOOK, a collection of craft essays published by Tin House. Aimee Bender’s essay on Character Motivation is one of my favorite.

“You shouldn’t be able to boil a story down,” Bender writers. “The elements of fiction should expand rather than contract. Two plus two should always equal more than four.”

I love that metaphor because for me, the pleasures of math and writing are opposite ones. I loved the clarity and definitive nature of solving an equation. There was AN answer, a landing spot. But in fiction—in poetry, in sentences, in text—there were a thousand directions and a thousand more landing spots. Fiction was not ‘correct’ when it landed happily any more than it was ‘incorrect’ when it landed tragically. Characters were not computers. Two characters could take the same action with drastically different results. Sometimes writers talk about there being a limited number of stories available to tell, but there are infinite characters those events could happen to.

So when talking about character motivation, especially in a workshop setting….we need to leave math at the door.

Because humans are messy as shit.

Aimee Bender gives us permission in this essay to GO AGAINST the common writing advice that you should know what your characters want. SHE SAYS IT’S OKAY TO NOT KNOW. And to let the writing be a process of discovering that instead:

“I don’t always know what a character wants. I know some things about the character, but to know what he or she wants feels like the final answer, why I’m writing in the first place.”

I remember reading a story in undergrad workshop that made me feel this way. It was a story written in reverse, with each section opening with the words “And before.” The opening scene was of a young woman drowning her baby in a bathtub. And as the story progressed, we moved backwards, seeing her pregnant, making sandwiches in the kitchen, her disappointed parents, dropping out of school. I don’t remember all the details but I do remember this sensation of feeling around with my hands in each scene, like….how could this gentle, hurt person do something like that to her baby? And maybe that’s how the writer felt moving through time too, exploring those complicated factors and knowing it wasn’t a simple one-to-one ratio. We get a big reveal at the end, which is the beginning: that it was her father coming into her room at night, raping her.

Part of the horror of this piece for me was that we never get a reason why—neither for the rape or the drowning. And it struck me, that’s how it is with much domestic or sexual violence—often the abused never really know why they’re being abused. It’s disorienting and terrifying. It’s part of the trauma. And in re-reading that piece, I could feel the razor edges to her scenes, that tender-footed-ness you get when you’re around someone you know might hurt you. You could tell there was something trapping or coercing the young woman, and you never get a clear answer “why” — there were lots of reasons. There were lots of razored edges.

In a lot of ways, allowing motivation to be messy is the same as allowing a character to be multi-dimensional. It’s about going in with like two pieces of information and kind of following your character around from there, seeing what they do. Seeing what’s in their purse, what they do in a car crash, how they break up over the phone. Aimee Bender says, “It’s about following hunches about character and really trusting those hunches.”

Maybe her best piece of advice is this: Allow for mystery. What she means is:

“Often writers will rush to an ending that completes, or sums up, or reduces their story as opposed to moving to a place where it goes to say something they may not understand and that may be incomplete but is more honest.”

For me, this often means writing BEYOND the ending. I say for me because sometimes I’m a little tender-footed about the unknown, and what I’ve found is that pushing beyond what I think is my final scene usually yields something much more strange and illuminating.