"Always the body was regenerating itself. Always it was dying."

Michelle Ross has given me a lot to think about regarding endings. Her stories are strong and lyric and potent - and the endings always feel sharp and jarring. I keep turning the page expecting more paragraphs because they END and they do not announce their ending. I am the bird sailing straight into glass. I am the coyote the moment he steps off the cliff, before he sees the abyss beneath him. I feel like I'm standing on the earth, then realize I'm not.

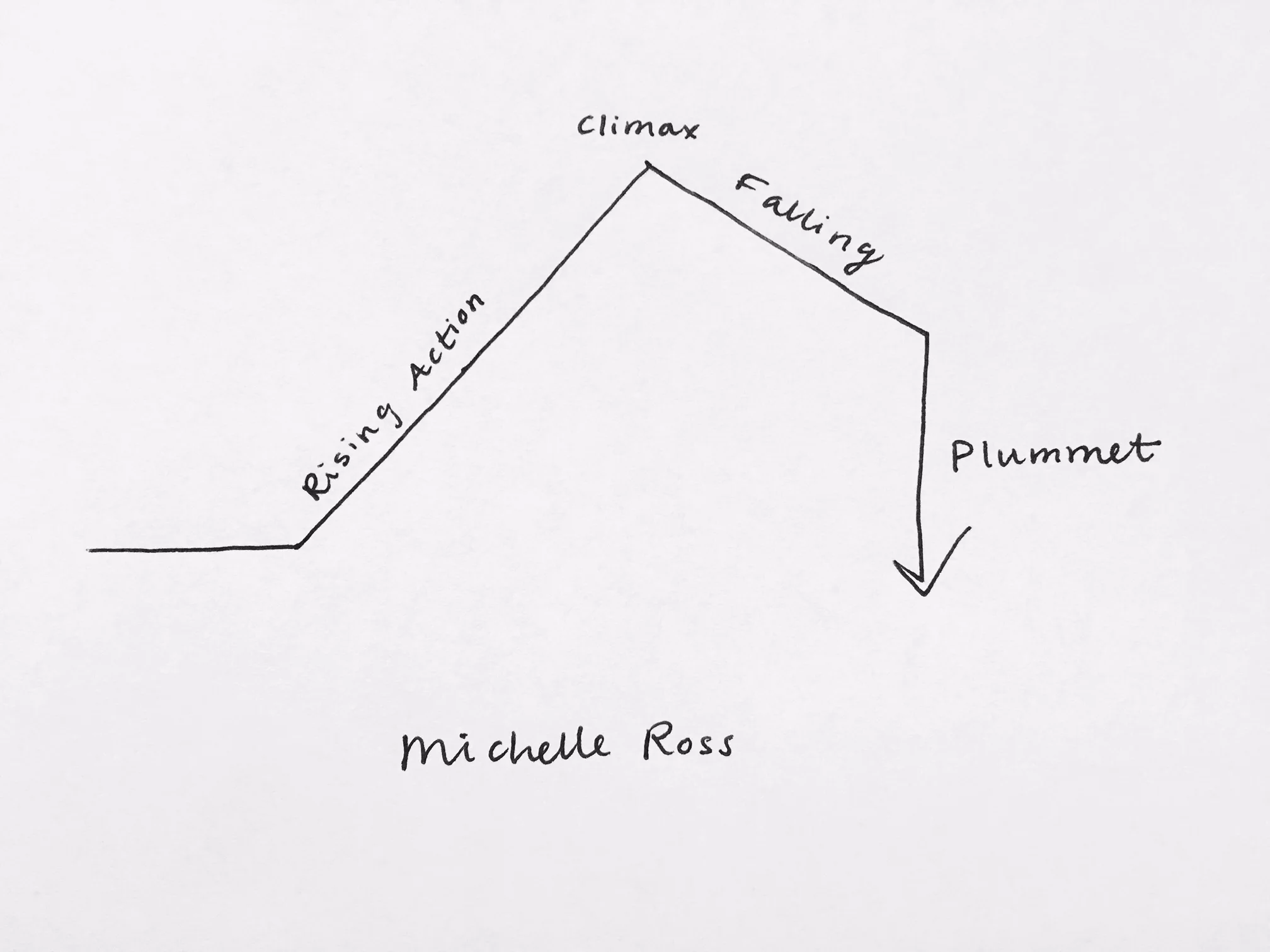

There's genius in this. It's strange to me, unconventional. Where is the denouement? The final outcome, resolution, "where all the secrets (if there are any) are revealed and loose ends are tied up"? Michelle Ross is keeping them locked up, or is opening the treasure chest and it's so filled with light we can't actually see inside. I feel like what Ross is doing is creating momentum in a plot arc where usually there's a flat line. Maybe the momentum is happening the second I go looking for more sentences. That's when I plummet, am sucked into some me-sized black hole.

This happens right out of the gate, in Ross' killer opener, "Atoms." Because the concept of atoms is rattling: "Nothing is solid in the way you formerly understood. It is mostly empty space...You are mostly empty space." The speaker is a young child, is swimming with that disarmed and alert and disoriented feeling: "you stand there and you stand there, the chalk shedding molecules all over your skin, molecules composed of calcium, carbon, and oxygen atoms, all atoms you already possess. You can no longer see the line between things." This feeling is not resolved or de-loosened at the end. Michelle Ross does the opposite. Michelle Ross starts her stories with a small tear that she then deepens. The seams flap open instead of being sewed shut. "Atoms" ends with the best possible question, "'There's so much they haven't told you. Don't you want to know?'" All of her stories end this way (for me) - I do want to know. I kind of love that block of white space. The refusing-to-tell-me.

I'm in the middle of the collection and have hit maybe my tenth glass-window, at then end of "Key Concepts in Ecology." There's a wild animal somewhere outside, and inside are the highly controlled and organized employees of New Zeniths. Outside are men in camo and daring delivery boys, there are bullets and an impasse of pines. Inside are the cubicles, the trapped wild-animals hearts of the workers (the finance who wants to get home, who insists their boss can't keep them hostage; the employees worrying over the birthday banners and the software updates and the rule-mandating employer; our protagonist, trapped in her job, in her relationship to an unemployable man, in the very building she's been advised not to leave, in her devotion to work-ethic, in her head - since she's not the kind of person who feels she can up and quit her job). This is the kind of story you read because you've been there - in the building you're not allowed to leave, in the job you hoped would fatten your account so you could do with your life what you intended. You're with the protagonist when she roots for the wild animal, when someone says, "I hoped they missed it. I hope that animals is fast," when someone else says, "If that animal's smart, it should be halfway across the state by now."

We root for the animal because, like the protagonist, we want that freedom too. That disrupting wildness. We want to be the unshootable thing (or I do). Some of us have fantasies about the kinds of wildness we don't see ourselves accessing. We're too practical. Resigned. We take our power in small victories, like slightly off-color birthday banner art.

But I do feel like the speaker of the story wants to be seen, and at the end she is, for a moment, real and untouchable as sunlight. Right before I smack into the glass.